Human societies have always sought better ways to exchange goods and services. From simple barter to today’s interconnected global finance, market economies have undergone profound transformations. By tracing key transitions, innovations, and ideas, we can appreciate how cities, nations, and individuals harnessed trade to create prosperity. This exploration illuminates the roots of modern markets and offers insights for navigating the economic challenges of tomorrow.

From Barter to Money: Early Systems and Innovations

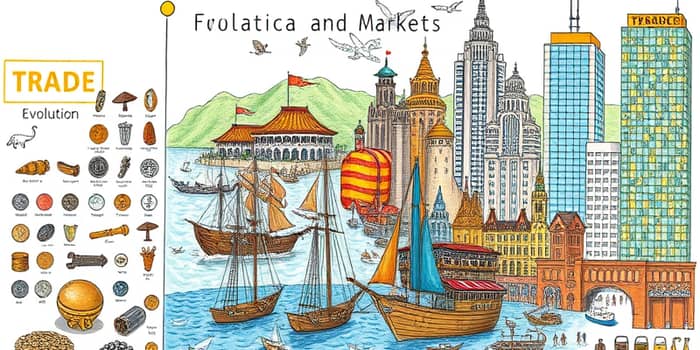

In hunter-gatherer and agrarian communities, trade began as barter—direct exchange of goods and services without a unifying medium. While practical in small groups, barter suffered from lack of a common measure of value and indivisibility of goods, making large-scale trade difficult. These limitations spurred the search for more efficient mediums.

Over millennia, various societies experimented with commodity money: cowrie shells in Africa, metal ingots in Mesopotamia, and early coinage in Lydia around 600 BC. By the Tang Dynasty (9th century), China introduced paper currency, which blossomed during the Song era and set a precedent for global adoption.

- Cowrie shells and metal ingots

- Coinage in Lydia circa 600 BC

- Paper notes in Tang and Song China

Medieval Trade, Accounting, and Financial Hubs

As commerce expanded, trade routes like the Silk Road wove together Europe, Central Asia, and East Asia. In Medieval Italy, merchants in Florence and Venice pioneered modern finance, establishing banking houses and formal markets. Their greatest legacy was accounting innovation.

The 15th century saw the birth of double-entry bookkeeping, which provided accuracy and transparency in complex transactions. This system—pioneered double-entry bookkeeping in Renaissance Italy—became the foundation for modern accounting, enabling merchants to track profits and losses across continents.

Mercantilism to the Industrial Revolution: Birth of Modern Markets

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, European powers embraced mercantilism, viewing wealth as finite and trade surpluses as a national goal. Joint-stock companies like the Dutch East India Company financed long voyages, while burgeoning stock exchanges in Antwerp and Amsterdam provided liquidity and risk sharing.

- Dutch East India Company (VOC)

- British East India Company (EIC)

- Early stock exchanges in Amsterdam

The Industrial Revolution (1760–1830) transformed economies from handcraft to machine-based manufacturing. With coal-fired engines and mechanized factories, goods flooded markets. For the first time, society experienced sustainable growth in living standards for the masses. Global nominal income rose to $100 billion by 1880, evidence of unprecedented economic expansion.

Commodities, Futures, and the Rise of Capital Markets

As industrial output grew, markets demanded standardized trading mechanisms. In 17th-century Osaka, rice warehouse receipts evolved into futures contracts at the Dojima Rice Exchange. The Chicago Board of Trade (1848) formalized grain trading and launched standardized futures in 1865.

Meanwhile, the New York Stock Exchange (1817) matured into one of the world’s largest equity hubs. Edward A. Calahan’s stock ticker (1867) democratized market data and pricing information, shrinking informational gaps and empowering investors far from trading floors.

Economic Thought: Theories Shaping Market Perceptions

The growth of markets inspired great thinkers to explain and guide economic behavior. In the 18th century, Adam Smith described the invisible hand guiding self-regulation of free markets, while David Ricardo formulated comparative advantage, underpinning international trade theory.

The 19th-century Marginal Revolution—championed by Jevons, Menger, and Walras—introduced marginal utility and supply-demand equilibrium. Contrasting these views, Karl Marx critiqued capitalism through the labor theory of value and exploitation, analyzing class struggle and systemic cycles.

- Adam Smith: The Invisible Hand

- David Ricardo: Comparative Advantage

- Karl Marx: Labor Theory of Value

- John Maynard Keynes: Demand Management

20th Century Turmoil, Regulation, and Globalization

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the United States emerge as an industrial powerhouse. Mass production techniques—epitomized by Ford’s 1914 assembly line—reduced costs and elevated wages. Banking panics prompted the Federal Reserve Act (1913), while antitrust laws curbed monopolistic power.

The 1929 Wall Street Crash and ensuing Great Depression challenged laissez-faire ideology. John Maynard Keynes championed government intervention, arguing that aggregate demand determines economic activity and justifying countercyclical fiscal policies to stabilize markets.

Post–World War II reconstruction, aided by institutions like the IMF and World Bank, fueled rapid growth. By late 20th century, GDP per capita had quintupled, and financial markets innovated with derivatives, options, and global capital flows, linking economies across continents.

Legacy and Future Directions

Today’s economies, valued in the tens of trillions of dollars, rest on layers of innovation from barter to blockchain. Each era taught lessons: adapt to new technologies, balance regulation with entrepreneurship, and foster inclusive growth. As digital currencies and decentralized finance emerge, the next chapter in economic evolution beckons.

By studying our economic journey, we gain perspective on resilience and innovation. Whether you’re an entrepreneur, policymaker, or citizen, understanding the past empowers you to shape a prosperous future in an ever-changing marketplace.

References

- https://www.preceden.com/timelines/67774-history-of-economics

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_history_of_the_world

- https://investoramnesia.com/financial-history-timeline/

- https://www.learner.org/series/economics-ua-21st-century-edition/economic-timeline/

- https://www.purdueglobal.edu/blog/business/us-economic-timeline-history/

- https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/rise-of-industrial-america-1876-1900/overview/